|

Book Cover

•

Table of Contents

•

< PREV Letter:

•

Book Notes

Letter: 23

Our Parents By Irma Howard Stolt

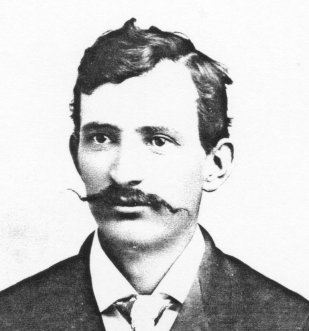

LEON DEWITT HOWARD

was born November 6,1870, the son of James Durkee Howard and Phoebe Ferris Howard, in Henry County, near

Atchison, Illinois. He came to Dakota Territory with his

father in 1883 in an emigrant railroad car with the farm

animals when he was 13. He, his father, his mother, his

sisters, Minnie Maud, Bertha May, Lulu Grace and his brother,

James Augustus, homesteaded in Summit Township, Sully County

where life was not easy.

For years they had to haul water, as they could not find water

from a well. Grandpa Howard's diaries always noted how many

loads of water Leon hauled each day. Leon was tall and strong

for his age and his father's health had suffered from his

Civil War years, so much of the hard, heavy work fell on Leon.

Later, Leon filed his own homestead. Leon sowed grain by

carrying the seed sack and broadcasting the seed by hand when

he was just a boy. In the winter, he started the day by

shaking the snow off his bedding in his attic room.

According to his friends and contemporaries, Leon was a

mathematical and mechanical genius. His college educated sons

could never stump him with their college math although he had

little formal education of his own. He was mainly

self-educated and had an abiding interest in science and the

Universe. Some of my fondest recollections of Papa are of

his demonstrations, using oranges, to explain the solar system

to us and his infinite patience in letting each kid have a

good look at the moon through his telescope. Also, hearing him

say "HARK" when he wanted to share something he was reading

with us.

At some considerable sacrifice, he subscribed to the

Scientific American magazine when in his teens and

continued this subscription for at least fifty years. It must

have pleased him when his U. S. patented invention was written

up in one of these Scientific Americans.

When just a little boy he worked long and hard on a perpetual

motion machine, an endeavor made even more difficult because

he was not allowed to use his father's tools. He remembered

trying to explain how he drilled a hole without admitting he

had used the forbidden brace and bit. At fourteen he invented

a knitting machine which his mother used for years. He shucked

corn for a neighbor for one dollar a day (his father got half)

and saved enough to go to the World's Fair in Chicago in order

to see the Scientific marvels of the age.

One day in 1900 when he was pitching hay off a hay wagon, a

little person came walking toward him. Papa said the sun was

behind her and her hair, a goldish red, shone like a halo and

he lost his heart to her, Zelia Spencer, the new little

"schoolmarm”. When he was courting her, he rode twenty miles

on his bicycle to Fairbank to see her but he said the really

great "sparking" was taking her out in the buggy and letting

the horse find its way home.

Leon and Zelia Evans Spencer were married June 19, 1901, and

they settled in Blunt where he set up his blacksmith shop and

later went into the hardware and farm implement business with

his brother, Gus, in their Howard Brothers Hardware.

Leon and Zelia lived all their married lives in Blunt with

Leon literally raising the roof of their one-story home, to

add a second story with four bedrooms to accommodate their

growing family.

Leon was president of the school board and fire chief for at

least twenty-five years. He was Marshall and a man to whom

people gravitated when they needed help.

He was a superb raconteur. His repair shop was a gathering

place for his yarn spinning and great good humor. He had his

home jokes and language — and he had his shop jokes and

shop vernacular and never the twain did meet. Harlow's wife,

Bea, used to toss pebbles at the shop window to announce her

imminent arrival so they could drop the shop vernacular. I

never heard him use profane language at home.

It is hard to describe Leon without waxing poetic. If I had to

choose one word, it would be unselfish. Both he and Zelia were

totally unselfish and honest and caring people. They lived for

their family and cared for their fellow man and their country.

One time I went to the shop to take Papa some lemonade. He was

in the process of taking a tramp to the restaurant where he

told them to give the man a good meal at his expense. When I

went home, mama was feeding another "tramp" in the kitchen.

Leon had the patience of Job. I never saw him lose his temper

- can you imagine that - a man with eight children. When he

said "Hark" we listened. He did show quiet desperation when

trying to get Aunt Fern to the train on time and once coming

home from Fairbank, he did spank us. After glorious encounters

with the river, the Grandparents, watermelons, rattlesnakes et

al, we were heading home in the seve-passenger Studebaker. I

used to sit on one of the little jump.seats. Mama said we were

making enough noise to wake the dead. Papa asked us to "Hark"

in vain and when one of us leaned out and tried to pick a

passing sunflower, he came to a halt beside a roadside

woodpile. With great deliberation he selected a paddle,

testing its tensile strength and resiliency by whacking it

loudly against his leg, while we subsided into stunned

awestruck silence. He marched us out of the car and gave each

one a swat — and that is the only "licking" I ever got

from Papa. Gene, being the baby, didn't even get that!

During his final sick years, many people came to see him and

to tell him they never would have made it through the bad

years without his help.

Leon worked so hard he had little time for hobbies, but his

yard was like a park and he loved trees. He planted trees for

each child and flooded everything from his own irrigating well

and old fire hoses. His strawberry patch was incredible. I

picked 300 quarts one spring when he was ill.

And then he loved working with wood which he garnered from

many sources. Using only hand tools for many years, he made

tables, desks, childrens' furniture . . . but most of all he

made rocking chairs of every size — even a double one for

"spooning”! He made a little rocking chair for me from a limb

of "my" apple tree he had planted for me. His sense of humor

came through even in wood working. A table he made for me has

a cherry top from an old Blunt saloon and the legs are from a

church organ. Another has a lovely top from the saloon and a

wrought-iron base made of a steering column from a car and the

iron bands from a barrel curved and welded in a lovely design.

And Leon was a reader. He loved to read aloud to us when there

was something he thought we should hear. Was there ever,

anything so lovely as listening to him read "Billy Goat Gruff"

while cuddled in his arms?

His family grew to eight children:

Leona, born April 2,1902

Loya Elaine, born February 14,1904

James William, born June 7,1905

Leon DeWitt, born February 15, 1908

Harlow Spencer, born October 28,1909

Helen Enid, born February 5,1913

Irma Fern, born April 3, 1915

Arnold Eugene, born July 30, 1917

For you who never knew him, he was a lean, handsome, six-foot

moustached man, so strong he could lift his anvil by the nose

cone with one hand. He was a soft touch for children. One time

he gathered up about 29 of the town children and took them to

the circus. As they trailed in under the big top, a clown

said, "My God man, are they all yours?"Papa said, "Every one”,

and in some ways they were. One of the last things he said to

me was to give "Old Timer" a silver dollar. "Old Timer" was

his five-year-old grandson, Robbie. Later, Robbie wrote in a

Most Unforgettable Person theme that he remembered his

grandfather not so much as a tall handsome man with a

luxurious mustache, but as someone who never condescended

— one who treated him, a five-year-old, as an equal. It

was a special gift.

Leon died on September 25, 1950, in the home that he had

expanded for his growing family. At his death, Zelia wanted

these words spoken of him: "A man skillful in his work shall

stand before kings”.

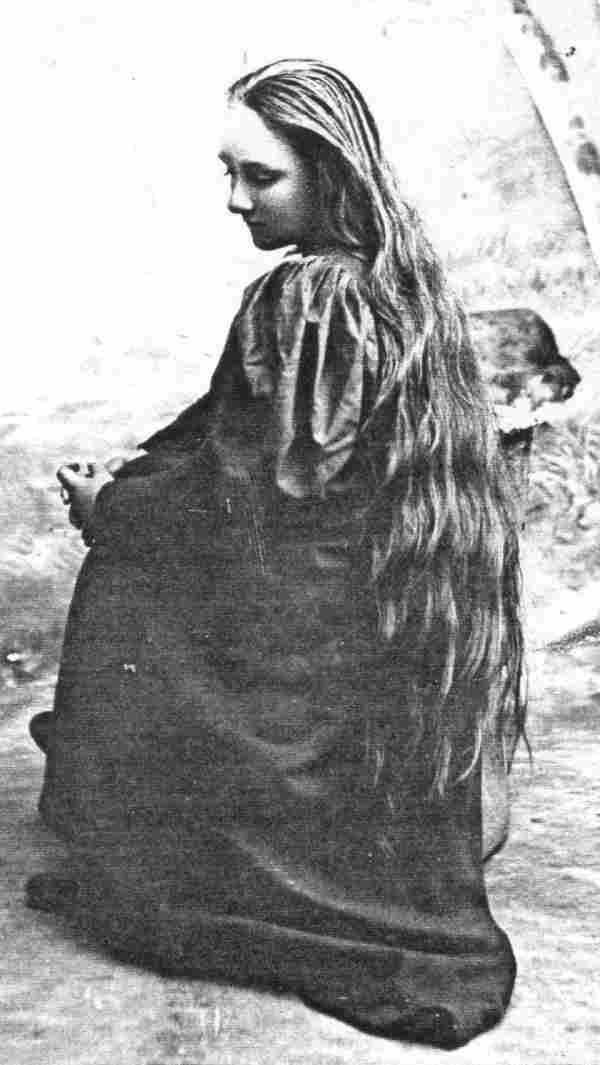

ZELIA EVANS SPENCER was born in Adams County near Payson,

Illinois, on April 19, 1882 at the home of her grandparents,

Samuel Moses and Jane Elliot Spencer. Her parents were William

Henry Spencer and Jane Evans Spencer, both mostly of British

descent. A Spencer ancestor, Thomas Spencer, came to American

in 1632 and the Evans ancestor in 1811.

Zelia, as a baby in arms, was brought to Rockport in Hanson

County, near Mitchell, Dakota Territory, on July 13, 1882. The

family lived there for two years and then moved to Potter

County from whence they moved to Fairbank Township on the

Missouri River in Sully County, where the family settled in

Fairbank House, a twelve-bedroom hotel, general store, and

post office. The store drew a large Indian trade from whom

Zelia learned the Sioux language. She remembered an Indian

"scare" in 1890 at which time she was taken to Gettysburg for

safety. She had one brother, Roy, and one sister, Mary Dean

Fern Spencer.

As a young girl, enduring the hardships and hazards of South

Dakota's intemperate climate, Zelia herded sheep. She was an

excellent horsewoman but the outdoor life was hard on her fair

skin. When she had daughters of her own, she always tried in

vain to protect them from the sun having suffered from it so

much herself.

She learned to read when she was four years old, a visiting

cousin having sensed her eagerness to learn. The family was

highly literate and had books and periodicals but she was such

a voracious reader, she read Dickens A Child's History of

England seven times when just a child. She attended

country school in Potter County and finished "common" school

under a tutor, Leon French. She took the teachers exam when

she was seventeen and earned her certificate. She taught the

Marston School for three months, which was the school term,

after which she attended Redfield College and Academy. Then

she taught Harris school one year.

And met Leon.

On June 19, 1901, she married Leon DeWitt Howard and they

settled in Blunt, South Dakota, where Leon had a blacksmith

shop. Eight children were born to this union: Leona, Loya

Elaine, James William, Leon DeWitt, Harlow Spencer, Helen

Enid, Irma Fern and Arnold Eugene. They were all born at home

with the exception of Gene who was born in the Pierre St.

Mary's Hospital.

In all the work of raising such a large family — cooking,

canning, clothing, cleaning, Zelia said she was never

discontented if she could find some time to read. Usually that

time was late in bed when her house was in order and her

family was finally asleep. She loved the English language and

her vocabulary was something to be reckoned with. Instead of

taking a bath - we 'performed our ablutions' and one time when

she said we "tracked the floor with impunity,"Papa looked

around and remarked that he didn't see any. He loved to tease

her!

In the hard years when she took in "roomers" — mostly

teachers — to help with college educations, Papa joked

that he didn't dare leave home as she might rent his side of

the bed. Well, one time he had to go to Watertown and was

going to stay over night but his plans changed and he came

back home. So, he playfully knocked at the door and when Mama

came to the door, he asked if she had a room for rent. Without

batting an eye, she told him her husband was gone and she

would rent his half of the bed.

In her voracious reading, Zelia's mind soaked up knowledge of

every kind. Her memory was phenomenal. One time when she was

in her eighties, an old friend Nellie Clark came to see her.

Zelia, in the course of their reminiscences asked Nellie if

she could remember the hard time she had learning the poem

about Noah and Mount Ararat. Nellie couldn't remember, but

Zelia proceeded to recite the poem learned more than sixty

years before. When I took her to her first art gallery in San

Francisco, she stepped into a room and said, "these are

Flemish paintings" — and they were. If you took her on a

trip and saw a sign about Jim Bridger or some such person, she

could tell you about him. Her interests were manifold.

Zelia was a pillar of the community. She was a charter member

of the Federated Study Club, was active in her Ladies Aid, the

Legion Auxiliary, the Good Neighbor Club and her bridge club.

Although very frugal and conservative by nature, she was a

holy terror to play bridge with, bidding recklessly, taking

chances and usually making the bid.

Her home became a central meeting place for social and

community occasions, there to enjoy her warm hospitality. In

order that the school kids could have banquets, she put all

the leaves in her table, rounded up her forty chairs and

served banquets for the junior-Seniors - the basketball teams

- so many things to give the kids a chance to dress up and

enjoy a lovely dinner with her best silver and china. She

baked so many pies that put side by side they might

circumnavigate the globe. That may be a slight exaggeration

but when she was baking for her family she always made extra

pies to be taken to old widowers, bachelors or someone "less

fortunate than we were”. Dwight Eisenhower said he was poor as

a kid but didn't know it. Things like mama's pies and her many

generosities made us feel the same way. When in her eighties

she still had as many as five different Christmas parties in

her home.

At one time, in an epidemic of smallpox, the house became an

infirmary for fourteen children. She was a good practical

nurse and she treated them all as her own. She also nursed her

mother when she was ill, brought home dour little Aunt Bert

for the winters, persuaded Grandpa Spencer to leave his

beloved Fairbank and spend winters in Blunt with her, and she

nursed her husband through the long painful years of his

illness, enabling him to die in his own bed in his own home.

Would you believe — and please do believe b— I never heard

my Mother say an unkind word about anyone. She never

complained. She was a good neighbor and a good patriotic

citizen. I remember her weeping during the Vietnam War when

she was listening to the song about Green Berets. Her

ancestors fought in the American Revolution and Civil War, but

she decided not to join the DAR when they refused to allow

Marion Anderson to sing in Carnegie Hall.

She died on the 29th of February 1972, at the age of 89. The

minister at her funeral said, "Zelia Howard was a saint”.

Mighty close, a dear warm earthly saint! She was a good wife,

a good mother, a good neighbor, a good citizen and a good

homemaker, gracious and kind and totally unselfish.

Her first great-granddaughter, Margot, called her "Great

Mother" and that is what she was.

Cover

•

Contents

•

< PREV Letter:

•

Book Notes

•

Page Top

|

BookStore

BookStore

BookStore

BookStore